THE BEGINNING:

I started on a journey about three years ago…or maybe it was five. I guess it depends on how you look at it.

In June of 2007 I moved to Seattle. I already considered myself a cycling enthusiast of the recreational and commuter variety. Hell, I even contemplated proximity to my workplace, as in safe and reasonably adjacent so I could use human-powered locomotion, when my wife and I looked for a place to live. I planned to throw myself (roll myself?) head first into the Pacific Northwest bicycle culture. I would ride to-and-from work, organize weekend outings to all the local cycling accessible sites, and participate in as many bicycle-focused happenings as possible. So I was pleased to learn that the regional bike club, Cascade, sponsored several events throughout the year. One of these was the Seattle to Portland, or the STP, as it’s affectionately abbreviated.

A short, and probably somewhat inaccurate, STP history: If you were to look at a road map, or use Google Earth, or break out your Encyclopedia Britannica, you’d realize that Seattle sits about 180 miles north of Portland. These two burgs are constantly locked in a struggle to out-cool each other. When it comes to cycling, I loathe admitting this, the city to the south has a slight upper hand. But that is beside the point…as I mentioned, if you were to drive it, you’d log about 180 miles. But, as I’m sure you know, a bicycle can’t take the same route as a car. Interstate 5 would be a dicey experience even if, only for a day, they allowed bicycle traffic. Therefore twisty back roads and multi-turn surface streets come into play. Over the years the actual course has changed a little, but it typically requires just over 200 miles of pedaling.

The first time the STP took place was in 1979 and it was a race, rather than a recreational ride. Currently, the rider limit is capped at 10,000 cyclists, along with a smattering of unicyclists and long boarders, and it always sells out months before the actual event. In 1980 it was cancelled because Mount St. Helens covered the route in volcanic ash; everyone rode to Vancouver, British Columbia instead (this ride also continues as its own annual event…it is called the RSVP). On the second Saturday of every July since, sometime between 4:30 and 7:30 AM, the participants roll up to the starting line and, in 15 minute waves, start their Seattle to Portland exodus.

The STP is promoted as a two-day ride, but approximately 15-25% of the riders knock out the distance in one day.

Also, considering elevation and route, it is not particularly a difficult ride. It barely crests 4000 feet, and all of this climbing, except for one hill in Puyallup, Washington, is evenly spread over the entire distance.

And what do you get for all your time and effort, your investment, both financial and intangible? A patch.

In 2008 I planned to ride the STP; two days seems difficult but obtainable. One day? That was just crazy! But the seeds had been planted…

FURTHER ON DOWN THE ROAD:

By 2010 I’d ridden the STP twice, both times in two days…2008 (134 miles on day one/69 on miles day two) and 2009 (150 miles on day one/53 miles on day two). In January of that year I pretty much decided that a one-day effort was in order.

Now is the time for some full disclosure: I considered hitting all of you readers with a blow-by-blow description of the personal disaster that was the 2010 STP. But after much consideration and contemplation I realized that this is a story unto itself. Let me just summarize, for about seven months I trained, strategized, trained some more, put together a team, did some more training, rode like my life depended on it, obsessed over the distance, organized and prepared food intake, pondered logistic needs and deficiencies, did a little more training, and, at the last moment…dropped out.

It wasn’t my choice. About two weeks before I wrapped my fingerless-gloved hands around the drops and pushed, pedaled, and powered my ride-of-choice 200 miles south I was diagnosed with a reoccurrence of my old friend, squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. It is a long story; I’ve been battling the disease for years, and admittedly, its sudden return with subsequent surgery was a legitimate excuse for withdrawing from the event. But deserting my friends and not getting to relish the rewards of all my sacrifices left me emotionally scarred and significantly depressed.

The ride, from what I interpreted from multiple impromptu post-STP debriefs involving copious consumption of delicious alcohol far removed from the paved torment that connected the two Northwest cities, was a completely new level of insane hell for all of my cycling buddies (I’ll always feel like I really let down my closest friend, Ivan) for several reasons. The 2010 STP wasn’t a disaster because of the cancer. It was a disaster because I was supposed to go and I didn’t; I feel my absence completely soured the experience for the members of the team I was closest to. Also, without me keeping everyone together, I was occasionally referred to as the glue, the group was destined to fall apart before reaching Beervana.

Enough about this…I promise, I will devote another entry to the 2010 STP debacle sometime in the future. But, I can honestly say, that low point is responsible for the website this blog is posted on. I needed a place to unload all of these feelings I had about the ride and it was important for me to share them with anyone willing to read and/or listen.

Also…

I knew I was going to return. I would have to ride the STP again and I would do it in a day.

TWO STEPS FORWARD AND ONE STEP BACK:

In January of 2011 I set my sights on making it the year that I crushed the STP, but it wasn’t meant to be. The same thing happened in 2012.

Just to be clear, when it came to the STP, 2011 and 2012 looked like carbon copies of each other. What did that look like? The best description I can come up with: big ass piles of failure.

Starting at the beginning of the year, sometime on a bitter cold winter morning, it was probably drizzling rain outside, I signed up, enthusiastically I entered my email and password into required fields on the Cascade website. For the next few months I rode 30 or 40 miles on the weekend, clocking an average pace of maybe 13 or 14 miles an hour, feeling and looking a lot like a circus bear on a bicycle. I would often tell myself that I would push harder when the critical spring months approached, but I didn’t.

Also, my attempts at reforming the team met with either disinterest or outright disdain. 2010 broke them. In my mind I could see them either lying awake in bed at night in a cold sweat or, worse, waking up screaming then immediately collapsing into a weeping fetal position; their only solace would come from being cradled in the arms of some caring loved one, a spouse or girlfriend, who is unable to truly understand the trauma they’ve been through. They all had some sort of post traumatic stress syndrome along with a 200-mile stare that intensified when the STP was mentioned. They were damaged goods and I couldn’t fix them.

By the time May rolled around I was too fat and way, WAY too far behind the power curve. My group was nonexistent. There was no way 200 miles in one day was in my future. Rather than punish myself, I admitted defeat. I refunded my STP entry fee, they keep a little off the top to teach the fool-hardy a lesson, and I cancelled my Portland hotel room reservation. By June of 2011 and 2012, rather than spending time in the saddle, I was on the sofa, enjoying the best Ben & Jerry had to offer and contemplating a new hobby…one with less sweat and more sweet.

ALL THE PIECES FIT TOGETHER:

But at the end of 2012 and the beginning of 2013 something different was taking place. Allow me to refer you to the previous blog post. A considerable amount of the heavy lifting had been done during my weight loss competition. In retrospect I realized that part of the problem, the reason I’d failed the previous two years, had to do with already being significantly behind the power curve when I started my training. This is difficult to admit…what I’m saying is, I was so out of shape that seven months wasn’t enough time to prepare for what most skilled and experienced riders could prepare for in (probably) half that time.

I know a lot of you are thinking that this is not the case and you may be right. But I knew where I wanted to be mentally and physically when I started the STP, and I know with a lot of effort and some hard work I probably could’ve been there. But in May and April of 2011 and 2012 I knew where I was and it wasn’t where I needed to be.

But this year was different. I was already 15 lbs. lighter than I was in 2010 and I’d pushed down on pedals all the way through late fall and into the early winter months. The day the STP registration opened in January for club members, there was no impending feeling of doom. Cold as ice outside and a warm glow coming from the fireplace, I put my entry fee into the online cart and hit the checkout button. In early February I felt strong on the bike and really fresh even after clocking 40 to 50 hard miles. I just had to keep it together, bump up my distances, stay healthy, and I would make it to P-town with the sun way above the horizon.

Over the next several months my preoccupation with the STP waxed a little, waned a little, then grew and grew and grew. I put back on a few pounds but I kept it well below my lowest numbers in 2010. I fixated and obsessed on several things:

Putting together a team: I made one big mistake in 2010. Using whatever tools I had at my disposal…bribery, begging, bullying…I forced a team together. It was way too big (about eight riders) and there was no connection beyond the bike. While two core riders were my friends, the others were barely acquaintances. Trying to keep them together, committed to each other, and focused on the group was like trying herd cats…on a bicycle. As promised, I will provide more details when I write about this period of my life on a future blog.

On February 10, 2013, at the Cascade bike swap during a spontaneous conversation with an ancient looking cyclist, he was like a bike-Yoda; I reluctantly disclosed the 2010 experience; even after two years the wounds were still fresh. He had five of the hard-earned one-day STP patches on display next to a smattering of bike odds-and-ends that were for sale in a scratched up glass case. I don’t know if the patches were on sale too, I assumed they weren’t considering how much I coveted one…if they were, I didn’t want to know. With just the right amount of compassion and respect, he informed me of my mistakes. “Just your close friends”…”no more than two other riders”…”your paceline will grow, you don’t need to bring one with you.” He educated me about keeping my cycling alliance small. These were words to live by.

And a team happened just like Mr. Bike Swap told me it would. There was Matt; new to the type of cycling we were doing, every week his abilities grew. And Steven, so dominant on the bike that we worried he’d hammer us to bits, but he showed amazing restraint when it was required. Brian shared my Coast Guard past. He was a triathlete, who could pull from a bottomless reserve of power. Like Steven, he was an intimidating force. Lastly, my good friend Ivan decided to ride at what was, in STP terms, the 11th hour. He was the only 2010 rider that would be joining us on the 2013 event. In late May he announced, unsolicited and out of the blue, his decision to give it another go. I was shocked. After his previous and somewhat dubious success, he announced his deep and everlasting resolution to never ride the STP again. This pronouncement oozed both sincerity along with a sincere hatred for what unknown things transpired during the 2010 STP. Why the change of heart? I have no idea and I didn’t ask. Best not rock the boat.

We lost one rider…Angie, my friend from the weight loss competition. Her reasons were valid. When she called me to tell me her decision I did my best to be as understanding as possible. I’d been there and I’d done that. You know that scene in Apollo 13 when Ken Mattingly (expertly acted by Gary Sinise) is unceremoniously informed that he could not go to space because he might get sick because he was exposed to some virus? Yeah…it’s that kind of disappointment. And while I know it crushed her, it definitely depressed me too. She was a big part of my STP world. I would go on and I already knew, in 2014 I would go again with her.

Considering Angie, this brings up an interesting point…allow me to digress for a moment. Lots of people drop out of the STP before it ever starts. A good percentage of riders know what they are getting themselves into (both one and two-day riders), they plan and train appropriately, and they make the trip successfully. There’s another group where life gets in the way and they decide, with prudence and wisdom, that discretion is the better part of valor. And there are individuals that, as they stand at the base of the proverbial mountain, have no idea how high and steep it is but start scaling it anyway. You see them, like bodies in the snow near the north summit of Everest, off to the side of the road, unable to go on. Or you watch, in abject horror, as they limp across the finish line, veritable minutes to spare before the whole even shuts down on day two. Their eyes are unable to hide the physical and mental pain that racks their entire being. It is best to know what you’re getting yourself into.

Let me get back on track…

Get faster on the bike/riding longer on the bike: I often admit to being a functional obsessive-compulsive. Many aspects of my life are charted in detail and planned in advance. I overanalyze things like the types, categories, and caloric content of the food I eat. I compare percentage of body fat gain or loss against absolute weight throughout multiple days, weeks, and months. I enjoy CONTROL! I know it is just perceived control…nevertheless, I like it.

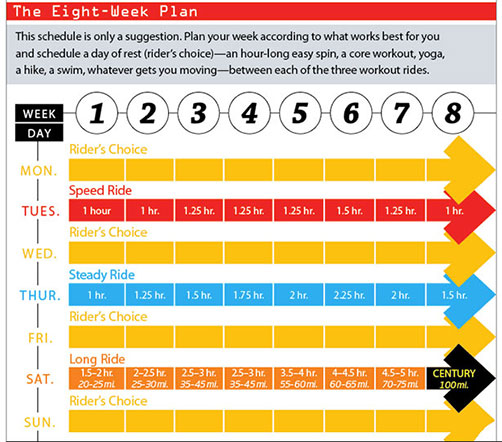

But cycling is different. I don’t want to scrutinize my riding; I just want to enjoy the ride. So there were no charts downloaded from a blog or cut-and-pasted from a top-end bicycling magazine. I just piled on the miles. Starting in April every time I went out for a weekend spin, I’d take the distance up a notch and go a little further than I did the week before. Also, I’d push myself a little harder.

FYI — I clipped this from the Bicycling Magazine website. Thanks, Bicycling Magazine!

What motivated me? Fear. You see, I’d experienced the bonk more than once and I’d witnessed it in other athletes several times. For those of you not familiar with this phenomenon, let me tell you, it ain’t pretty. It is comparable to running your engine at full throttle until it prematurely explodes. I did not want to blow up at mile 50. Also, I had two genuine and all-to-realistic concerns that were pressing with every pedal stroke: first, what if my team had to leave me behind, too slow to keep up with their pace? Second, the finish line closed at 9:00 PM on day one. What if we found ourselves several miles away from our goal with only minutes to spare? The level of frustration and regret would be vast and immeasurable. Admittedly most of this fear was based on the unknown along with the embellished accounts from my 2010 team. But the bottom line: I had to…I HAD TO…make it to Portland while the finish line was still manned with volunteers still handing out the much sought after one-day patch.

I got faster and I went further. Of course a lot of this had to do with keeping the weight off, but there was no replacement for time in the saddle…period. I rode and rode and rode.

Logistics and Strategy: what did I have to do when I wasn’t on the bike? Lots of stuff! Like the events of 2010, putting it all together deserves a post unto itself, mostly for posterity and education. I know that there are riders that just ride. And on the day of the event, they show up at the start line and several hours, or a day, later they show up in Portland. Everything goes fine and they have no problems, except maybe the occasional flat. But this is not how things go for me. Remember that OCD? I plan.

Also, there were long discussions with my team about pacelines and projected speeds. We also strategized about how often we would stop and where. Cascade, along with an army of unpaid helpers, do an amazing job with their organized support stops. But a rider can lose whole hours eating Clif bars while chatting with a volunteer making PB&Js. It was critical to not let this happen to us.

THE DAY APPROACHES:

In the preceding weeks before the event I felt readyish. Overtraining is concept that is somewhat nebulous to me. Wikipedia defines it as “a physical, behavioral, and emotional condition that occurs when the volume and intensity of an individual’s exercise exceeds their recovery capacity. They cease making progress, and can even begin to lose strength and fitness” and Wikipedia is always right. I’d been riding a lot so one might argue that I’d overtrained. Personally, I just felt like I was tired of riding the flippin’ bike. 125-mile rides required a full day on the weekend, typically starting at 5:00 AM. Do six of those and your favorite pastime becomes more of a chore. By the time the day approached I was ready for it to be over.

Also, I realized all of my fellow riders were faster than me. If you’ve ever been the slowest rider in a pack you realize what this means. You end up having a lot of uncomfortable “please don’t leave me behind” conversations, each ending with an assurance that this will never happen. But cyclists can be like unbroken stallions. Once they are out of the corral, they demonstrate very little control.

And in the back of my mind crept the Fear. Would I die on the vine or would time crush me under its never-ceasing boot? The Unknown has a tendency to enhance the Fear.

The day before the event several of us met at my home. We grilled some meat, drank some beer, watched the Tour de France, and discussed, like Vikings before a battle, where we’d been and where we were going. Ready or not, this was going to happen. My bike was washed, a fresh coat of Proofide was deep into the scarred and seasoned black leather of my Brooks saddle, the chain, gears, and cables were lubed, and the tires were inflated to a tense 105 PSI. My wife’s car was loaded with the foods and provisions that would support us past mile 100. That was where most riders stopped on day one; we would find little organized aid south of Centralia, Washington. I laid out my Jersey, now sporting my number, along with my most comfortable socks, and bib-shorts. At around 6:00 PM I dosed myself with an Ambien, nervous energy made it next to impossible to fall asleep without chemical aid. Even with this pharmaceutical assistance, unconsciousness did not come easily, but by 7:00 PM I was out.

The morning of the ride I rolled out of my deep slumber at around 2:45 AM. I wanted to get up early, hoping to avoid feeling rushed before the ride. Matt, not looking forward to having to wake up an hour before everyone else, decided to crash at my place rather than his home far north of Seattle. He was up and around shortly after me. We were quiet, just going about our business, contemplating our upcoming adventure.

We ate a light breakfast of crockpot oatmeal, it was a recipe I downloaded from the Internet, it had the consistency, texture, and taste of banana infused paste. Brown sugar made it palatable, but just barely. Just FYI: I deleted the recipe bookmark before I left that morning.

At 4:15 most of my team mustered at the top of NE Ravenna Blvd. This would give us a smooth and relaxing roll to the Huskies Stadium parking lot where the start line was waiting for us.

I can’t speak for my fellow riders; I just know how I felt. First, my emotions were very different this time compared to the feelings I had before my last STP rides. Two-days, two centuries, I always felt comfortable with these times and distances. But this morning in July of 2013 I had a barely controlled sense of excitement along with a looming fear of failure. For events such as these, for every rider, there is no guarantee of success; far from it. Over the past few weeks, for me, aches and pains that were little more than a bother were now amplified, and they would get worse the farther I got from Seattle. I would be out there with 10,000 other riders, some would be careless, accidents happened. Was my machine up to the task or would I have a critical failure? If I did, God forbid it should happen while I was screaming down some hill. I wondered if this is what it felt like before a mountaineer summited a 8,000 meter peak, or an astronaut sat on the Launchpad, or a soldier readied himself for combat. I should stress, I’m not comparing my ride to such amazing feats. But, just a little bit, I understood what it felt like to stand before a simultaneously dreadful and awesome undertaking.

As I rolled down Ravenna hill, I found some comfort thinking about all of the darkened homes I passed. They were filled with people, still sleeping. They were going to wake up in a few hours and if they were fortunate, go about their usual and occasionally mundane errands, maybe watch a little TV, walk their dog, or what have you. All the while, I would be on an adventure of a lifetime, riding my bike 200 miles!

Matt, Ivan, and I found our way to the start line and met up with Brian and Steven. We positioned our bikes behind a long line of riders, about 100 yards from the makeshift strut-and-beam gate. If you’ve ever run a marathon or done a century ride, you’re familiar with the structure I’m talking about. Getting through it is all the riders cared about. All of us rocked back and forth on cleated shoes and stiff muscles. All of us were ready to get this started. At 4:45 the first wave rolled out. A hundred or so cyclists shuffled and half-pedaled there way forward at a low-speed, ready to rocket out after clearing the improvised enclosure. Our hope was to be in that group but the ride organizers brought the first wave to an end before we could get through. We were less than five feet from the corral exit and the actual start. Approximately ten minutes later they let the next wave go. At 4:55 we were on our way.

THE RIDE:

The first several miles of every cycling event go by fast. Initially my primary goals are to avoid crashing and to keep my group together. Riders weave and jockey for position without much thought, water bottles find their way out of loose-fitting cages and on the route, groups of cyclists cluster and restart at every red light and stop sign. We were like salmon, doing our best to swim upstream in the time allotted.

There were moments early on that made me pause and consider the day to come. When I crossed the University Bridge I was treated to Seattle lit by sunrise light. I stored the image away in my head so I could compare it to the skyline of Portland I’d hopefully be viewing in about 12 hours.

Here are the highlights from our ride:

- Lake Washington Ave. saw our group hit 20 MPH for the first time. We would stay close to that speed most of the day.

- We pulled into the REI food stop at mile 24. It was part amusement park, part shantytown. We were directed where to park our bikes and then ushered by several canopy covered tables laden with all sorts of foods designed with the athlete in mind: bars, gels, fruits, bagels, etc. Awesome classic rock, I think it was Steve Miller, was blaring out of multiple speakers. A disc jockey was keeping the crowd entertained. We topped off our bottles and emptied our bladders…we were out of there in about 12 minutes. Mission accomplished!

- At around mile 30 we decided to make a quick pit stop in an office park. When signaling that I was going to make a right turn I slapped another rider. I am pretty sure my finger went up his nose. If you are reading this, rider I slapped, my apologies.

- The dreaded Puyallup hill at mile 45 wasn’t nearly as bad as I thought it would be. Ivan and I climbed it together at a brisk pace, talking most of the way.

- The next 50 miles were smooth, leisurely, and uneventful. On the bike trail through Yelm we linked with a paceline that had us topping 25 MPH. Speed is sweet.

- We rolled through Centralia at mile 100. This is the mega-stop. Most riders call it a day near this small Washington town. Crowds were already gathering and long lines were forming at every food stop, port-o-potty, and water bottle top-off station. Fearing a long layover, I pushed my team to head out as quickly as possible. The good news was that I’d prepositioned a food stop just seven miles down the road. My wife was there with a Subaru filled with delicious and nutritious goodies. Brian and Steve, basing their decision on my reassurances, decided to hold off on filling their water bottles.

Ivan informed me after the ride that this was the moment, around 100 miles into this STP, he entered into his dark place. All long distance riders and endurance athletes experience this at one time or another following a period of extended exertion. It is when they question their decision, in retrospect, to partake in another long ride and consider every option, finding an air-conditioned diner and waiting for a ride back home for example, rather than continuing with some epic endeavor. Often, if pushed or confronted during these moments, tempers will flare and arguments may happen. During this particular period I was never aware that he dipped into uncertain blackness and it passed without incident.

My dark place would come much later.

- Shortly out of Centralia, as we passed over Interstate 5, I got my first view of Mount St. Helens. This is my second favorite part of the ride.

- Seven miles later I realized that my wife was actually fourteen miles from Centralia. From that moment forward I would be know as “seven more miles”. I pointed out that my bottles were still half full; this just made things worse and everyone got a little more pissed at me. But overall our moods were still good.

From front to back: Matt, Brian, Ivan, and Steven.

- In Napavine my lovely wife set up an improvised rest area under a shade tree. We spent about 20 minutes eating sandwiches, stretching out, and filling long-empty water bottles. We all headed out feeling pretty strong, definitely ready to conquer the last 85 miles.

- I am of the opinion that mile 115 to mile 150 is the worst part of the STP. Why? Well, it is a no-man’s land of mini-climbs, chipseal asphalt, and wicked narrow shoulders. I was targeting mile 151: Longview and the Washington-Oregon border.

- In Castle Rock we stopped at the Coast Guard two-day campsite. I am a retired Coastie and several of my shipmates were a few hours behind us. We topped off our bottles, stretched again, and headed out.

- In Kelso-Longview we met up with my wife and again, we refueled. This time, after our 20-minute stop, I found it much harder to get back on the bike. My legs were starting to shred and fatigue was getting the best of me. But all that was left was 50 miles. I knew, even on my worst day, I could crush 50 miles.

The Lewis and Clark Bridge over the Columbia River marks a huge milestone in the STP. Right before going over we agreed to muster on the other side. There was some confusion exacerbated by a wrong turn as we approached the run-up to the overpass. I rolled into Oregon unaccompanied, my team about a quarter-mile ahead of me. The downhill on the other side is remarkably fast and dicey, made worse by four-foot wide expansion joints. It is a rush.

- The next 45 miles was where I started to come apart. My team went into overdrive, like horses headed back to the barn. There were scarcely any other cyclists on the route, only other one-day diehards. Through most of the day, mile 1 to mile 150, we blended with other pacelines. Now we were alone and leaning hard on each other. Our speed was up…WAY up…constantly touching 25 MPH. While I was able to hang on flats, I fell off the back on just about every hill. Fortunately our training and previous strategy discussions kicked in. Every few miles, when necessary, we would regroup. In the distance I could see the dark place.

- We stopped at St. Helens, the last organized mini-stop for one-day riders. The watermelon was delicious.

- At around mile 199 we climbed the last big hill that took us to NW St. Johns Bridge. My legs were shredded, my tank was empty, and I was firmly entrenched in my dark place. Once we were over the bridge, while stopped at a red light, I told Matt that I wanted to keep it slow for the last few miles, however many there were. He agreed. I also told him I wanted to throw up.

- At Mile 200 a small child was holding up a sign that said “only six more miles to go.” Every fiber of my being wanted tear up that sign right before I beat the crap out of his father. Remember, the dark place.

- The ride through PDX was a pleasant red-light-to-red-light experience. Each stop allowed me to rest and refill my tank a little. It is a beautiful, scenic city and it was a perfect day. My mood was smoothing out and I was feeling better. I had three miles to go. I could carry my bike that distance.

- There was one last climb about 200 yards before the finish, but it wasn’t too bad. We rolled as a team into Holliday Park to cheering crowds and joyful loved-ones at around 6:30. I got my patch.

What else is there to tell you about? The next few days were blissfully anticlimactic. I didn’t hate the ride or my team members. Actually, the opposite was true: within minutes of finishing I knew I’d be back in 2014 and I would be more than happy to do it with them again. On Sunday we woke up early, ate a big breakfast, and hung around at the finish line waiting for our Coast Guard brethren to finish their two-day journey. They finished around 1:00 PM. I recognized the elated look in their eyes. Mine had looked the same just a day before.

Over the next few days, at every opportunity, Matt, Ivan, and I recounted our adventure. I was happy to hear that Ivan shook his 2010 demon. This time after the STP he felt optimistic and confident, his soul no longer tortured. All three of us were impressed with how fortunate we were; not one flat, the weather was picture-perfect, and all of us felt injury-free. Our overall speed amazed us but we new we could do it faster. During one long day in July of 2013, for five guys riding bicycles on a road that ran between two cycle-centric cities in the Pacific Northwest, the stars aligned and the bicycle gods touched their spirits. The most important thing: we’d set out to do something big and we achieved our goal. It just took me five years to do it.